Kan nilaog siya sa harong

arog kan awot na ginabot sa magapo

dangan tinanom sa maray na daga,

kan su sinaray niyang isog nawaran ki kamugtakan,

nagadan na man su pagmawot niyang mabuhay.

Sa imbong kan mga lanob

na daing lipot na pigpapalaog

luminatang su saiyang tulang

na napupungaw sa pangangaipo

ki paglakop.

Su lawas niyang dai na nahihigot

ki punaw buda pakig-agaw,

huminewas sa rasay

kan ubos na mga laogan.

Ta hali digdi kuminamang

an dakol na burak kan buru-banggi

niyang pag-utob

sinurop su saiyang sapog.

Natada saiya an masakrot

na duga kan pag-alang.

Dangan siya buda an bintana

pagturog na an gabos

pigsasapar an haldat kan imon

sa layas na mga bituon.

Saro siyang awot

na ginibong tinanom.

Tabang saiya an panahon

na maako an saiyang pagkatanom.

An saiyang ogma mga ngipon

kun kaipuhan niyang pahilingon.

Naubos na

su saiyang mga ngipon.

Sa balkon kan saiyang pagsulnop,

pighiling niya su laog kan saiyang kamot.

Pigsusog duman su mga dalan kan salog.

Punas na kan haloy na dai pagmawot.

Bago abutan kan diklom

luminuwas siya sa harong.

Naglakaw na daing kiling,

na garo dai nang kikilingan

sagkod maabot

an lugar na daing kasiguruhan.

An kadlagan

kun sain sana siya may kasiguruhan.

Duman an paghangos

na haloy pinugol

giraray pinunan.

Enero 10, 2007. Pawa.

Translation:

A story of a weed

When she was housed

like a weed pulled from rocks

then planted on fertile soil,

when her kept wildness lost its sense,

death came to her will to live.

Under the warmth of walls

which allow no coldness

her bones became lacy

longing for the need to spread.

No longer tightened

by hunger and competition,

her body loosened in a fall

of empty containers.

For from this crawled

many flowers of her nightly

obedience

sucking her sap.

What was left of her is the bitter

juice of dried-ness.

And when everything is asleep,

she and the window

suffers the burn of jealousy

for the wild stars.

She is a weed

made into a plant.

Time aids her

to accept her plant-ness.

Her happiness are teeth

when she needs to show it.

She lost all her teeth.

In the porch of her setting,

she stares at the inside of her palm.

Tracing there river paths.

Erased by the long absence of desire.

Before darkness reaches her

she steps out of the house.

Walks without looking back,

like there's nothing there to look back for

until reaching

a place of uncertainty.

The forest

where she has certainty.

There the breathing

that was long held

is again begun.

An istorya kan sarong awot/ A Story of a Weed

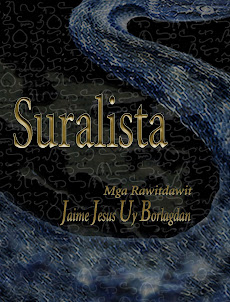

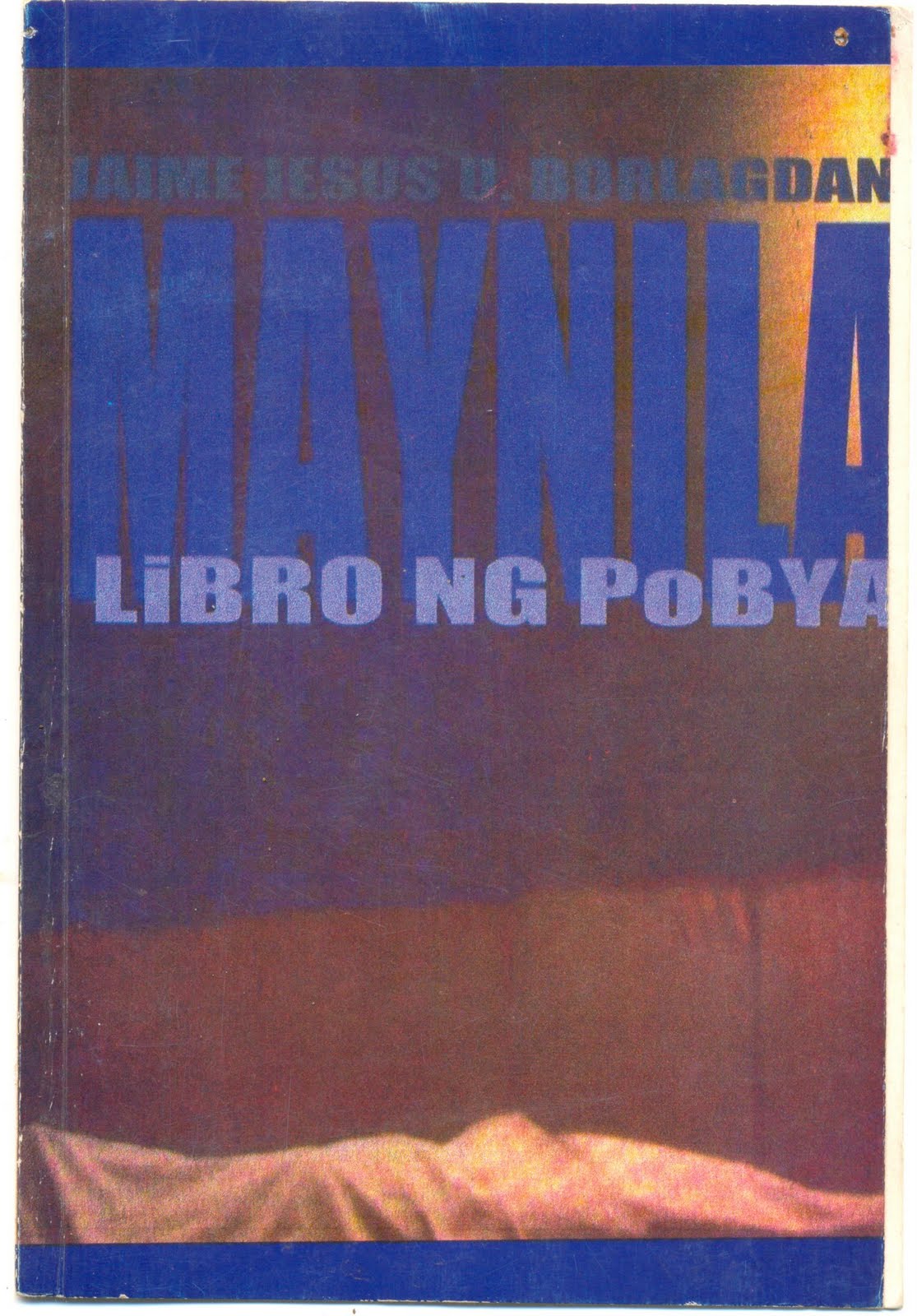

Posted by

Jai Jesus Uy Borlagdan

Sunday, February 15, 2009

0 comments:

Post a Comment